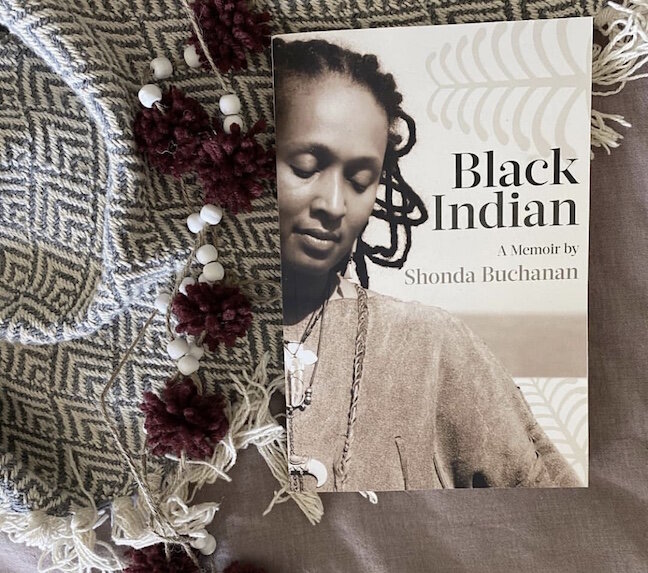

Black Indian

The Sunlit Project and UNUM Magazine present HER JOURNEY, a narratology mapping the unique and universally-shared experiences of women’s extraordinary journeys.

“This Sunlit Project developed during the worldwide pandemic over my kitchen table, but the idea of mapping women’s journeys began with my own, as a migratory mother, driving a thousand miles westward. I encountered commonalities and differences within the Hero’s Journey, a mythologically-informed template that identifies the classic elements of a “journey” - a call to something more, obstacles, a supreme ordeal, transformation and more - but it overwhelmingly centers a male archetype. Thus, HER JOURNEY seeks to lift the “her” in the Hero’s Journey and identify what makes it uniquely and universally female.”

-Sun Cooper

Growing up, my mother never used the term Black Indian. She always said, 'You've got some Indian in you, some French and German, and a little bit of Black.’ So I lived my life according to what she said, but I also lived in the role society prescribed to me by my race and gender.

As a descendant of African Americans, American Indians, and Europeans, Shonda Buchanan's journey is one of reckoning with multiple inheritances. Many of us identify with a predominant identity and the familial stories we were told growing up; but Shonda’s story begs the question: if we point to various places on the map to locate all of our ancestors, how many of us would find conflicting histories of loss, removal, immigration, slavery, indentured servitude, settlers, and conquest coursing through our blood?

In a conversation with UNUM, Shonda provokes answers that are both medicine and a knife, the kind Langston Hughes describes: Let us take a knife and cut the world in two – and see what worms are eating at the rind.

Having grown up on a rural farm in Michigan with the kind of childhood that recalls a “weeping willow” with the same metaphorical memory as the tangible one, Shonda is now an award-winning author, educator, mother and grandmother who resides in California and has traveled to over 12 countries. Like many, COVID has slowed her adventuring; but she’s been on the road since she was 18. It’s not the farm girl traveling the world that makes her journey remarkable; but her courage to cross the deep racial divides rutted throughout the topography of her own ancestry and America’s, unflinchingly detailed in her book, Black Indian. Having navigated it and lived to tell, she has emerged with a vision to help us get well.

Wrapping sage, California, IG photo provided by Shonda Buchanan and @feisty_feminista

Preparing for ceremonies, California, IG photo provided by Shonda Buchanan and @feisty_feminista

SC: When did you first sense a "call to something more"? Describe that moment for us.

SB: There are several, but I'll isolate one moment. When I was 9-years-old, I bought myself a pair of chopsticks from the Kalamazoo Public Library where they had all kinds of interesting artifacts in this glass display box. From that moment, besides reading everything I could get my hands on, I felt that my calling was cultural: researching and sharing my culture and also learning other people's cultures.

SC: In your memoir, you share an unusual journey as a woman exploring her legacy of multiple inheritances: Black, Native, and White. Can you talk about the crux of this inheritance with us?

SB: My feeling of inheritance is connected to and centers around absence. As a Black person in America with the legacy of enslavement, I know I have inherited the precepts of the times that permitted such egregious acts against Black bodies, particularly Black women. My pride in being an African American, and also in the strength of Black people is fierce. Simultaneously, I celebrate my American Indianness because of all that we have lost in the colonization of our lands. This country was strategically pulled apart and relabeled without consent of the Indigenous population; I feel that loss and absence of traditions every day. As a writer, I try to turn that around and look at the rich legacies I have inherited and that fuel me … as a writer, as a woman, as someone who continues to practice the traditions of my people on all sides. I use the feeling and knowledge of absence and loss as a place of empowerment.

SC: In your book, you bring up powerful talking points about racial formation in the U.S. under the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, something you've described as "a racial invention on a sheet of paper." In your own experience, aligning with one identity was sometimes seen as a betrayal of another. You and your family "never fit neatly" in a census box. How has this box been a significant obstacle in your journey?

SB: Being bi- and tri-racial feels (to some) as if you are watered down. The obstacles I have faced – in declaring and celebrating my ancestries and heritage – sometimes come from the very people who look like me, whom I love and adore; but who want me to choose a side. It's always been difficult to think that I would be forced to choose which culture to celebrate. This ideology is intrinsically divisive to people of color; it's also a direct result of colonization. If we don't look at the origin of the illness we can never treat it. We will never heal from it if we can't name it.

We have fallen apart and away from each other so that we are divided, splintered, and forgetful. We ourselves have forgotten that our blood carries the truth.

A walk with sage and memory, from the Black Indian book trailer by Protius James

Drum, from the Black Indian book trailer by Protius James

SC: Did you find yourself forging your own path outside of that census box or did you find help along the way?

SB: I found a lot of kinship and mentors along the way as I got older – people who were also in search of the secrets of the past and their ancestry. As a younger person those ideas were just things that I knew existed, but I never interrogated them. When I started asking questions, I discovered some people didn't want to remember the past, so they put up roadblocks that I've had to dismantle over the course of my own research and writing.

I was a cartography lesson. I was the geography of the intersection of enslaved Africans, Eastern Shore American Indians, indentured white servants; their journey was on my face. I was the seed of a memory that my grandparents wanted to forget.

SC: It seems like such a small personal moment, when music inspires you; but you’ve shared how a particular song symbolized a portal, which led you from Michigan to California, and eventually 12 different countries.

SB: The day I first heard “Dust in the Wind,” I was young, on a farm, and just waiting for life to happen, or waiting for something good to happen. The song made me feel something else was out there in the world, that I could form a different kind of identity, and not just be the child who came from a family that happened to be violent. When I left, I felt as if I was a flower petal in the wind; I really had no plans of what I was going to do. Los Angeles became a safe haven for me and still is.

I close my eyes

Only for a moment and the moment's gone

All my dreams

Pass before my eyes with curiosity. – Kerry Livgren, Kansas, "Dust in the Wind"

SC: Have you encountered a supreme ordeal? If so, does it mirror a supreme ordeal that your ancestors have encountered?

SB: Nothing that I have encountered mirrors the supreme ordeal that my ancestors had to face. I have not been stolen by a bushwhacker looking to sell any person of color into chattel slavery. I have not been a slave who had to have sex with a white slave master, to produce a child that could also be raped by a white slave master and then sold away from me. I have not walked the Trail of Tears nor suffered at Wounded Knee. But I write about them because the memory is something that I dream about. Writing about my ancestors gives me a way to give them back their voice, their dignity, their solace, their privacy and, ultimately, their lives. I do feel that growing up in a violent home is a result of the things that happened to my ancestors – the things my mother and sister experienced, and the molestation that I experienced – I do think these are direct results of the past.

SC: A unique element seems to surface again and again for women, that intuition is a deeply significant part of Her Journey. You've written about "a collective, inherited gift of sight." Can you talk about this inherited gift?

SB: For the women in my family, we have always had a unique gift of sight. Some people call it second sense. Some people call it visions. Knowing this is probably something I inherited from my great-aunts and grandmothers made me feel special. It also made me pay attention to my intuition in dealing with people. That's not to say that I always made the best choices … but my intuition has served me, and my dreams have helped me manifest a life I couldn't see yet but knew I could have.

SC: In every classic journey, there is a return home. You "once had a vision in a dream of a line of ancestors in the sky, leading [you] back ... home." What does returning home mean for you?

SB: The ultimate returning home means all my women are safe in one house on the same land, eating the same good food, laughing and telling good stories about our lives. Knowing that the land I'm standing on is ancestral land and no one can remove me from it. Coming home means I have built a space, a homestead of some sort where all my people can come for a refuge and never be harmed.

Instead of staying sick, we'd help ourselves get well.

My Nations: I’m 11th generation Coharie, Eastern Band and Delaware Cherokee and Choctaw, and of course African from Senegambia, before colonizers renamed and disrupted us. Yes, there’s European blood too. All my relations got me here - Aho! Picture courtesy of Shonda Buchanan

SC: Do you have medicine for those who find themselves at unique amalgamations of their own ancestries? Do you find hope in these multiple inheritances for understanding and shared progress? How do we “help ourselves get well?”

SB: I find medicine and hope in both my African American and American Indian ancestries because I've realized this is the kind of work, like writing, that feeds me and keeps me sane. When I do writing workshops or lectures across the country or internationally, I always mention how writing and researching my heritage has given me a sense of power. I believe that a part of my getting well deals with empowering myself with my ancestors' stories. And that is my recommendation for anyone who feels unbalanced … to start writing about the people who kept you alive, the people who dreamt about you before you were born. That sense of connectivity and sustainability of your family name and your blood is priceless. No one can take that from you, even if you experience prejudice or are subjugated or discriminated against. No one can take your blood inheritance. Walking with that kind of knowledge makes me both humble and strong in this world. Makes me know and understand that I am not just speaking for myself. I'm speaking for the cacophony of RedBlacks who fought, suffered, and died; but also survived, so that I could be here to tell their stories. Aho.

My lifeline was the rock that would not break under the hammer of time. I had returned. I was still here.

****All quotes and the following blessing are excerpted and shared with permission from Shonda Buchanan’s memoir, Black Indian:

This is life or death, sister, Turtlehawk, one of my elders, told me on the first day of my Vision Quest …It is at once a reflection of your relationship with the Creator, God, Yahweh, and the relationship you have with yourself. What you are made of. What you must overcome ...

Even the rock breaks in the fire. In life, you have to decide what to let leave before you break … It is hard … It is life.

I am a rock in the fire.

It's a good sweat. Mitakuye Oyasin.

All my relations.

Black Indian tablescape, IG photo provided by Shonda Buchanan

This feature is dedicated to Shonda’s daughter, grandson and all her relations.

And to those “in search of the secrets of the past and their ancestry.”

Find more info on Shonda at https://shondabuchanan.com. You can watch the book trailer here and buy her

award-winning book Black Indian here.

About the author: Sun Cooper is a migratory mother, published author, and multicultural literary consultant. Her work and collaborations have appeared in People Magazine, Rolling Stone, National Geographic, Hill Lily, American Cowboy, Southern Writers, and Severine. With her amalgamation of Cherokee, French, Basque and American West ancestry, she identifies as a storyteller, mother, and sojourner who asks for the wisdom of ancient paths while migrating her own. You can find her at www.sunliterary.com/thesunlitproject.com